The way in which Gauteng’s social development department has treated nonprofits’ funding this year reminds, to some extent, of the provincial health department’s conduct in the Life Esidimeni saga. Lisa Vetten writes why it’s important that government’s decision-makers be held accountable.

Gauteng’s Life Esidimeni tragedy — in which over 140 state mental health patients died and the judgment in an inquest handed down on 10 July found the negligence of high-ranking provincial health department officials was to blame in at least nine cases — makes it clear why it’s important that decision-makers are held responsible for harm stemming from poor administration decisions.

And, sadly, the way in which Gauteng’s social development department has treated nonprofits this year — which essentially do the government’s job for them — reminds us to some extent of the province’s health department’s conduct in the Life Esidimeni saga.

Public administration determines who gets which state resources, when, and why. When it comes to care for people who need a social safety net, like older persons, victims of gender-based violence (GBV) or people who struggle with substance abuse, it’s a power to be reckoned with.

In the Life Esidimeni case, nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) became instruments of destruction because of administrators’ rash decisions.

According to the health ombud, five such organisations to which state mental health patients were transferred from a private hospital, were especially ill-equipped to offer them the specialised care they needed.

The Gauteng health department’s late payment of subsidies compounded this. For weeks, they had no money to buy food, resulting in malnutrition and hunger, strongly contributing to many of the patients’ slow deaths.

Has Gauteng learned from Life Esidimeni? Not so much, it seems

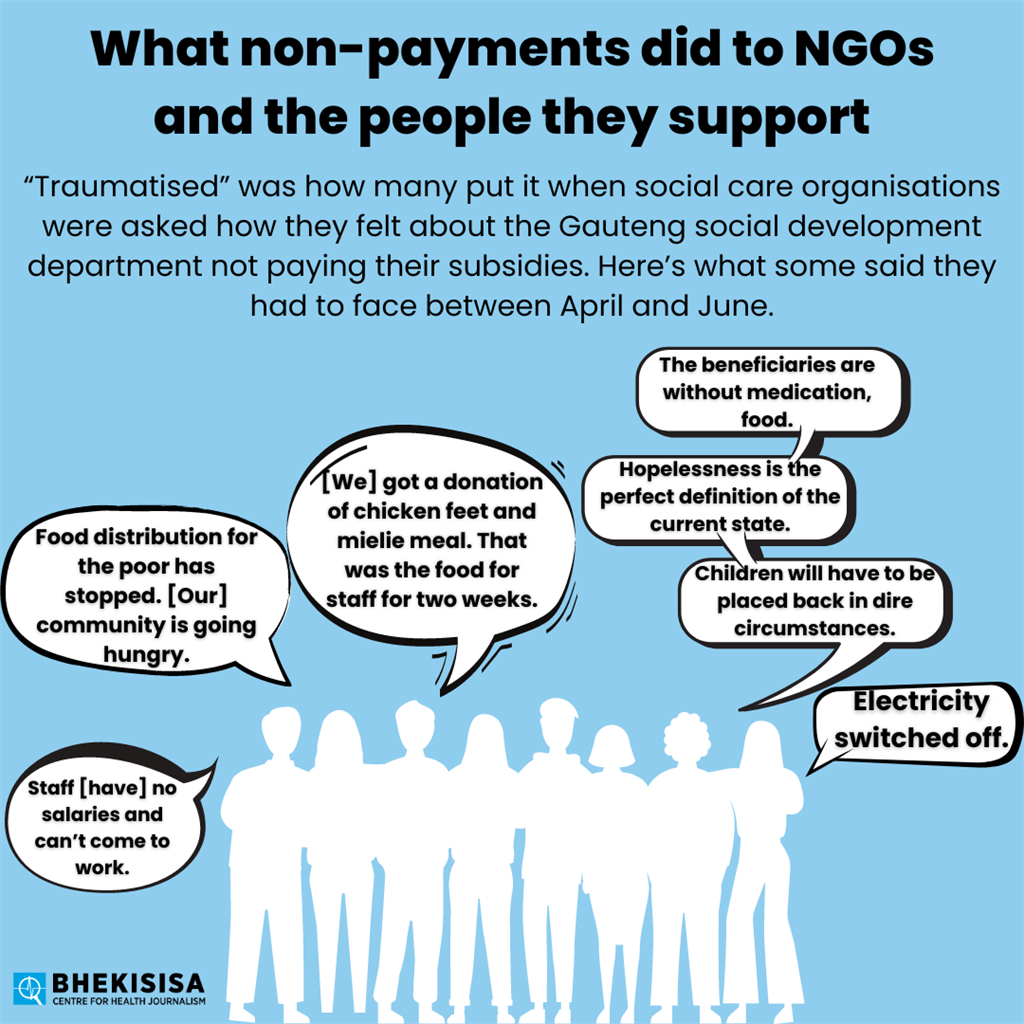

Eight years after Life Esidimeni, we are, yet again, experiencing the devastating consequences of the Gauteng government paying NGO subsidies late — or not at all.

In this case, it’s not a specific group of people who have to bear the brunt, but rather the system that offers help to people who need social protection.

Like schools and universities, such organisations get government subsidies, which they use to care for — on behalf of the state — children who live in precarious social situations, GBV survivors, people struggling with substance use or those with disabilities.

Their projects boost the ability of the social development department to honour the rights of vulnerable persons to food, dignity, social assistance and freedom from violence.

Unlike the Life Esidimeni NGOs, which were hastily and unlawfully registered by the Gauteng health department to provide care, the nonprofits funded by the social development department have been key to the province’s system of social care services for at least three decades.

But earlier this year, “serious missteps” in calculating NGOs’ subsidies and the subsequent payouts caused the sector such “pain and misery” that the premier of Gauteng, Panyaza Lesufi, had issued a public apology on 3 July.

It followed after the social development department claimed, in late 2023, that the Auditor-General had found serious shortcomings in the department’s administrative controls of the nonprofit funding process, which called for wide-ranging changes in approach.

Decision-making powers were withdrawn from the five regional offices and centralised in the provincial office, which then took control of all 1 700 applications for funding. With no experience in handling these matters, and without the necessary systems in place at the provincial office, the process congealed in a chaotic muddle, worsened by budget cuts.

And so, instead of organisations receiving their contracts from the social development department by March and their funding by April, as had been the norm, NGOs entered the new financial year with no certainty about their futures.

In response to organisations’ wanting clarity on when they’d know their fate, the department wrote that those “who are successful will be informed accordingly before the end of the month of March, in line with the [d]epartment’s projections” and asked them “to conduct themselves in an orderly manner”.

How is the Gauteng government being held accountable?

Civil society had to intervene to keep the government accountable — not unlike the outcry after the Life Esidimeni tragedy.

The Gauteng Care Crisis Committee, presenting more than 60 unpaid NGOs, took the provincial department to court in May to force them to wrap up evaluating applications urgently and let organisations whose funding has been approved know within seven days of the court order.

The judge ruled that the department had to finalise the evaluation process by 24 May, have service level agreements in place a week later and pay out funds within seven days of the agreements being signed.

Nonprofit projects help to create hoped-for worlds for people who have none. Many of these projects are also a labour of love. To discover that these worlds, and those who live in them, were both expendable and redundant when the welfare organisations didn’t get their funding caused its own kind of injury.

Caring became a liability. Because of the admin bungle some organisations had to let staff leave, because the cost of caring had become too high. At others, people had to learn to care less, simply to protect themselves.

The premier’s apology was, in some way, a recognition of the harm done to the sector and its beneficiaries. The appointment of Faith Mazibuko as the new MEC for community safety is also an opportunity for a fresh start.

What has to change?

Gauteng’s system of care can be repaired, and the injurious power of administrative processes can be limited.

The National Social Development Department’s sector funding policy already guides how the funding process should be run. Gauteng needs to draw from this framework to correct the “serious missteps” it has made since 2023.

In line with this policy, services must also be costed and budgeted for, as organisations’ funding has not been increased since 2022. This would both recognise the value of NGOs’ work and ensure that the people they support get the quality of help they deserve.

The department taking responsibility for its “serious missteps” is necessary — especially as the auditor general has publicly denied telling them to change the approach to funding NGOs.

Public administration is not glamorous. But when used well, it has real power to get money to the right places and people and so fix inequalities and the shortcomings they create.

But the other side of the coin is also true: if applied badly, these powers become just one more source of harm to people living in precarious circumstances.

– Lisa Vetten is a gender violence specialist

– This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.

Lisa Vetten

www.news24.com